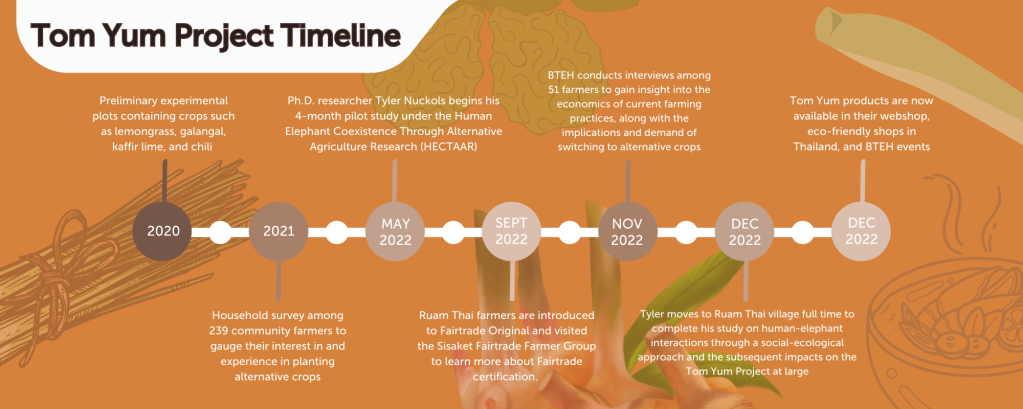

Lemongrass, galangal, kaffir lime, and chili – these ingredients of the Tom Yum soup, a classic Thai dish, don’t simply remain in the bowl. They also play a role in facilitating human-elephant co-existence. Our partner in Thailand, Bring The Elephant Home (BTEH), began the Tom Yum project in 2020 to help support the local community by designing and implementing experiments using alternative crops that are unpalatable to roaming elephants. In 2022, we also welcomed Ph.D. researcher Tyler Nuckols of The University of Colorado, Boulder in Ruam Thai for a first 4-month pilot study on the potential of alternative cropping as a method to promote human-elephant coexistence, which will contribute to the completion of their Ph.D. dissertation. Three years after its conception, this project has grown from helping farmers alleviate economic losses to a profitable and eco-friendly venture. What’s going on in Ruam Thai nowadays?

Experimental alternative crop trials

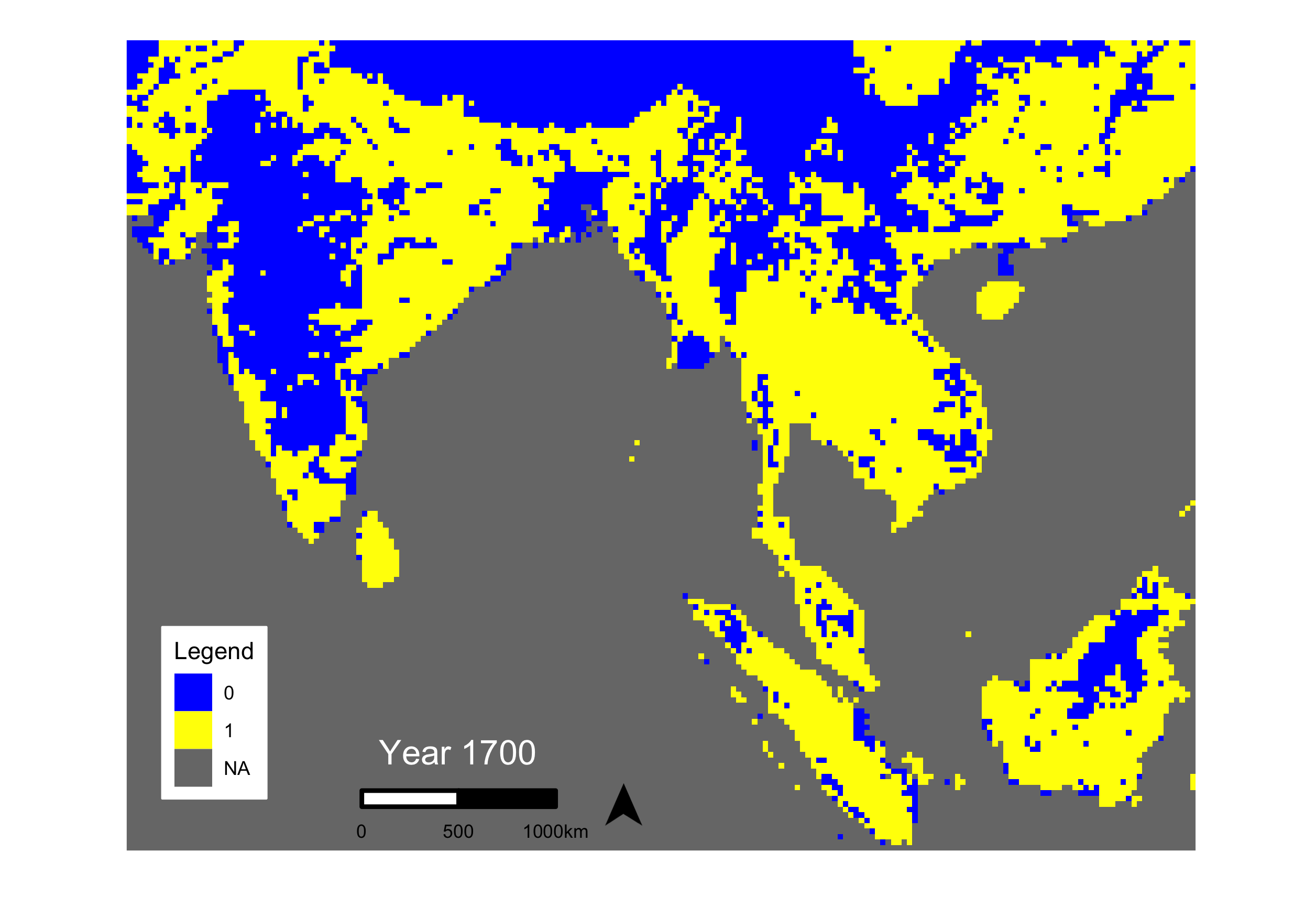

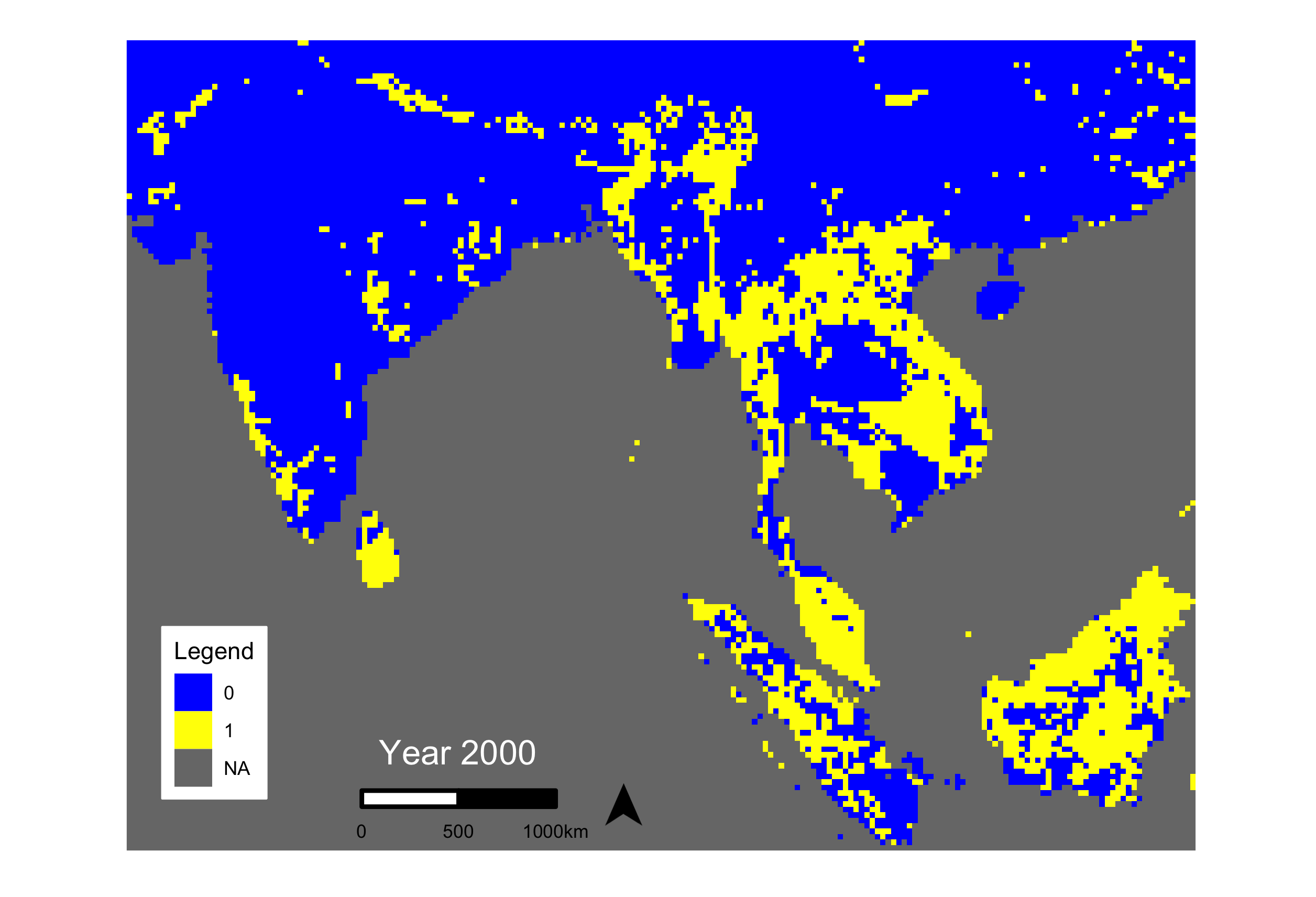

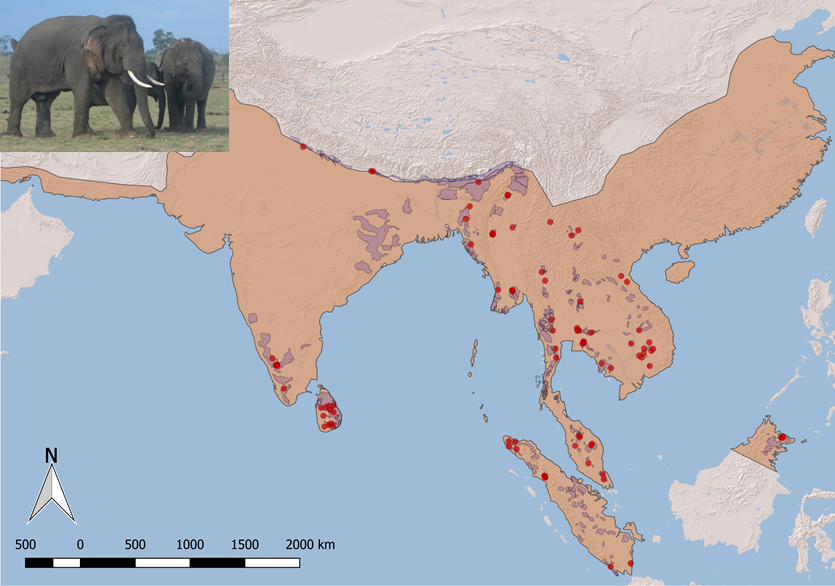

In 2020, BTEH kickstarted the Tom Yum project with preliminary experimental plots containing crops that are believed to be unpalatable to elephants. Preliminary results of BTEH’s Country Director Ave Owen’s research showed that among the crops planted, lemongrass and citronella experienced the least damage from elephants. These two crops were also resistant to insect-transmitted diseases, drought, and other environmental factors that impacted the yield of other experimental crop species. Furthermore, no damage was recorded when elephants walked through the experimental plots; spending little time there, only to make their way to neighboring pineapple plantations. We believe that as the alternative crop project grows, elephants will have less incentive to enter human-dominated areas, and if they do, farmers won’t experience such devastating financial losses as they did before.

Right: The first major harvest of lemongrass and citronella from the Tom Yum project experimental plot

The community’s pulse

Between Aug and Sept 2021, Ave Owen conducted a household survey among 239 community farmers to gauge their interest in and experience in planting alternative crops. The majority (90%) of participants reported negative experiences living near wild Asian elephants and expressed willingness to switch crop species to reduce crop damage from wildlife.

A year later, in Nov-Dec 2022, 51 interviews were conducted among pineapple farmers to gain insight into: the economics of current farming practices, and the economic barriers that could discourage farmers to transition to alternative crops. In line with the interviews, BTEH also evaluated the minimum and maximum market value for pineapple, lemongrass, and citronella to gain perspective on the potential economic impact of transitioning to alternative crops. By doing so, they were able to plan community interventions that not only mitigate human-elephant conflict (HEC) but also caters to the people’s economic needs, by finding a reliable and fair market. While full analysis is an ongoing task, data gathered in these questionnaires and interviews are used to optimize the potential impact of the project to conservation and the community.

“Elephants have already pushed over all the trees in my land and the land of neighboring farmers. If we can plant these [alternative] crops like how the farmers are doing here, we can all keep farming without worrying about elephants.” – Khun Noot

“Our land is different and our weather is different, but I want to try planting these crops and if there is a guaranteed market I think other farmers in our village will want to try too.” – Khun Sak

Human Elephant Coexistence Through Alternative Agriculture Research (HECTAAR)

Together with a research affiliate of BTEH, Tyler Nuckols began working in Ruam Thai in May 2022, first for a 4-month pilot study. And eventually moving to the village full-time by Dec 2022 to complete their study on human-elephant interactions through a social-ecological approach and the subsequent impacts on the Tom Yum Project at large. Tyler first sought to test and improve their research methods, gain firsthand experience with the focal study location, network with community members, listen to local experiences with elephants, and complete a preliminary social-ecological inventory. During this pilot field season, Tyler accomplished the following:

Visited Kuiburi National Park regularly to document and understand the community-based safari and tourism program as well as observe the wild Asian elephants

- Worked with Ave Owen to learn previous methods, and understand current study designs and data collection processes, such as crop damage enumeration

- Guarded crops with farmers at night, conducting semi-structured interviews and observing Asian elephant activity in crops employing new night vision technology

- Met with the Chief of Kuiburi National Park for introductions and preliminary discussions

- Joined educational coexistence walks to learn firsthand about the human-elephant conflict present in the Ruam Thai community and farmers’ perception toward elephants

- Learned the process of creating elephant-friendly value-added products and participated in the harvest of experimental lemongrass and citronella plots together with the community

- Joined national park rangers, WWF staff and farmers in a community weeding of the national park border observing the park boundary and paths elephants use to crop raid

- Together with Brooke Friswold, a Ph.D. candidate of King Mongkut’s University of Technology Thonburi, developed trail camera data collection methods

- Met with the Village Chief of Ruam Thai to gain research permissions, make introductions, and conduct a semi-structured interview

- Conducted five semi-structured key informant interviews in Ruam Thai

- Co-hosted two focus group sessions to gain feedback on our social science tools and conduct informal interviews with participants

- Conducted 30 surveys with randomly selected households in Ruam Thai to gather baseline data and test the instrument.

Following the pilot study and preliminary data analysis, Tyler has adjusted and reframed their study to address the following questions:

- What are the areas of highest elephant presence, activity, and crop damage in our focal study location of crop fields surrounding Kuiburi National Park?

- What social and ecological conditions result in vulnerability to human-elephant conflict for smallholder farmers, and how does this vary across the landscape?

- How does the practice of growing mono-crop pineapple compare to a regime of crop species unpalatable to elephants in terms of changes in measurable farmer vulnerability and adaptive capacity?

- Is there a significant difference in elephant presence, activity, damage, and repeated individual visits between farms growing mono-crop pineapple and those pursuing nonpalatable crops and varying levels of measured household vulnerability?

Their study aims to create a model that combines social, spatial, and ecological data to identify hotspot areas of high HEC, human vulnerability, and elephant activity to target management and mitigation solutions. The community in Ruam Thai and management team of Kuiburi National Park, will have full access to this model and map. After the study’s conclusion, the smart AI camera trap network can serve as an early warning system in crop fields surrounding the national park.

The importance of Fair Trade

In September 2022, BTEH connected with Fairtrade Original in the Netherlands. Fairtrade Original closely collaborates with farmers in Thailand, assisting with training and capacity building to aid farmers in getting Fairtrade certified, a visual guarantee that farmers and producers are fairly compensated for their labor. Once certified, farmers can begin collaborating with a factory in Bangkok to export the products to the Netherlands.

As a first introduction to Fairtrade Thailand, representatives of Ruam Thai’s pineapple growers visited the Sisaket Fairtrade Farmer Group (FFG), part of Fairtrade Original, and learned valuable lessons. The farmers in Ruam Thai have experience in growing alternative crops for personal use, but not so much as a cash crop. They were eager to hear more about how the Sisaket FFG grows these crops commercially, and more importantly, the value of fair trade, and how this model can contribute to the well-being of individual farmers, as well as the community. Counting 12 years of experience with Fairtrade, the Sisaket FFG shared their knowledge with great enthusiasm.

Ruam Thai farmers learned about what it takes to become Fairtrade certified; they visited certified farms and left with invaluable insights and inspiration. The second step to certification involves a site visit of Fairtrade Thailand to the village. During this visit, environmental conditions such as availability of water and use of chemicals in the farms will be inspected along with the farmers’ knowledge and experience in planting the alternative crops.

This could be a game-changer for Ruam Thai farmers, the Tom Yum project, and in realizing human-elephant coexistence. We are grateful for the hospitality and guidance of the farmers in Sisaket and the guidance from Fairtrade Original.

Capacity building and product marketing

Whenever there is an opportunity, the Tom Yum Project community group sells elephant-friendly products and shares stories about how alternative crop initiatives help realize human-elephant coexistence. The Tom Yum Project team attended a SEED replicator program and learned about previous successful Eco-Inclusive enterprises. Our team also had a chance to present the history, challenge, and vision of the Tom Yum Project.

The Tom Yum products are for sale at their webshop , and now available in six eco-friendly stores in Thailand.